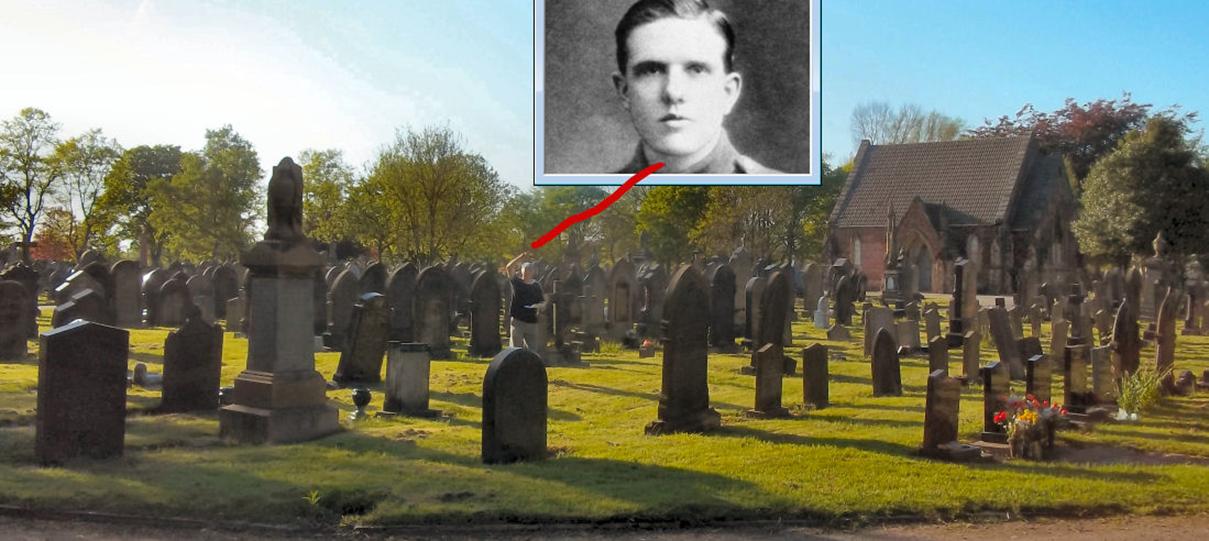

Alfred

Wilkinson (5th December 1896 to 18th October 1940)

I didnít expected this graveyard in Leigh to be so vast. I thought Iíd

ďnip inĒ on the way home from a long weekend in the Lake District, find the

grave and soon be back home to quell the hunger pangs. I ended up walking

around for nearly an hour.

Strangely as I pulled up outside the main gates someone was pulling up

driving the same model of car in the same colour. The occupants looked

scruffier than me and I didnít fancy them nicking the wheel trims off my car

(even though the whole three-piece suite on wheels is

only worth £450.) I got chatting to them and, as locals do, they scanned over

the photo I had of the headstone I sought then directed me to an area nowhere

near the headstone. Iíve learnt to ignore peopleís guesses as to where grave

lie.

Though the cemetery sprawled over acres I found the headstone by

matching up an oddly-shaped tree in the photo with the tree itself (and there

were a blooming lot.)

Alfred was born in Leigh not far from his final resting place, working

in a mill with his dad as a cotton piecer (dangerous

job, leaning over rapidly moving spinning machines to repair broken thread.) At

21 he was fighting in France in July 1916. He was a private in the 1/5th

Battalion, The Manchester Regiment and fighting in the Battle of the Selle.

On 20th October 1918 at Marou in France

three troops were advancing against heavy German guns - without success. The

troop Alfred was in was pinned down by enemy firing from a sunken road from 50

yards. Heavy machine-gun fire was coming at them from front and right flanks

and many men lay dead by their sides. Realising help was needed volunteers were

requested to go back to headquarters to fetch more men. Four volunteers had

already scampered across the 600 yards of open country to the reserve line -

and four men had been slaughtered and now lay dead in the grass.

Alfred volunteered knowing the 600 yards was a killing floor and

anyone trying to cross its deathly measure was volunteering to die. Heavy

machine-guns and bombs rained on any soul in German cross-hairs. Somehow Alfred

made it in 15 minutes to raise help. How I wish you could go to a website and

see this happening from a birdís eye view. Again he dodged cross-crossing

bullets to return; this 30 minutes of his life must have welding itself into

his brain for the rest of his life (which wasnít long.)

On 8th February 1919 Alfred was given two weeks special leave to

return to the UK to receive the Victoria Cross. Arriving at Leigh railways

station he was welcomed home by the Mayor and various townspeople. They put him

in a carriage pulled by horses and took him to the Town Hall escorted by

mounted and foot police, a detachment of soldiers from the guard at the Leigh

prisoner-of-war camp, Boy Scouts, St Johnís brass band and various discharged

soldiers and sailors. At the reception he gloriously celebrated and given 500

War Savings certificates and £50 in cash (later also a gold watch.) Alfred was

a quiet unassuming man who didnít like attention so this must have been an

uncomfortable day for him (later on he declined nearly every offer to take part

in any public affairs.)

In February 1919 he travelled to London with his mum and brother to

Buckingham Palace to receive the Victoria Cross from King George V. After the

ceremony it was back to Belgium to re-join what was left of his old battalion.

Though he gained a Victoria Cross Alfred had lost lots - his eldest and

youngster brothers and his dad all died in the war.

After the war he was employed by the Leigh Operating Spinnerís

Association. Leaving the arm Alfred worked for the Leigh Operating Spinner's

Association. They were bombarded with criticism when they docked Alfredís wages

when he went to attend a Victoria Cross Reunion Dinner in the House of Lords

(he was duly reimbursed.)

Alfred married Grace when he was 35 and they had a daughter. They

bought a sweets and tobacconists shop but gave it up shortly before the

outbreak of the Second World War.

Sadly there came a stupidly early death at 43. Alfred joined the Bickershaw Colliery in Leigh as a laboratory technician but

on 18th October 1940 he was at work complaining of a headache and wondering

whether to go home. At noon he was found dead. The pathologist reported death

by carbon-monoxide poisoning (a dead sparrow was blocking the flue from the

furnace.) Iíve learnt only people can dispense fairness as kismet and anything

almighty doesnít: after years fighting people who would kill him without

thought Alfred was indirectly killed by a sparrow.

The streets of Leigh were lined with spectators to watch the

impression cortege pass, three deep in places. The Knights of St Columba, the Special

Constabulary and the British Legion had each asked to carry Alfred to his last

resting place. He was lowered into the same grave at his dad with full military

honours. The black marble cross Iím stood by here was paid for by The

Manchester Regiment and Wigan Borough Council.

In 2006 Alfredís Victoria Cross was bought at auction for £110,000 by

Lord Ashcroft (who collects the crosses - one day I hope he comes across my

website as Iím trying to get round all these brave folk.)

In the car I had a coffee and slither of chocolate to hammer

the hunger pangs (wheel trims had not disappeared.) I was glad there was a

red wreath on Alfredís grave; good to know someone else is ensuring these brave

folk arenít forgotten.

With his mum and brother HenryÖ

Touching the ďVCĒ and there it is on

his chestÖ

The funeralÖ