Grave

- George Stephenson (9th June 1781 to 12th august 1848)

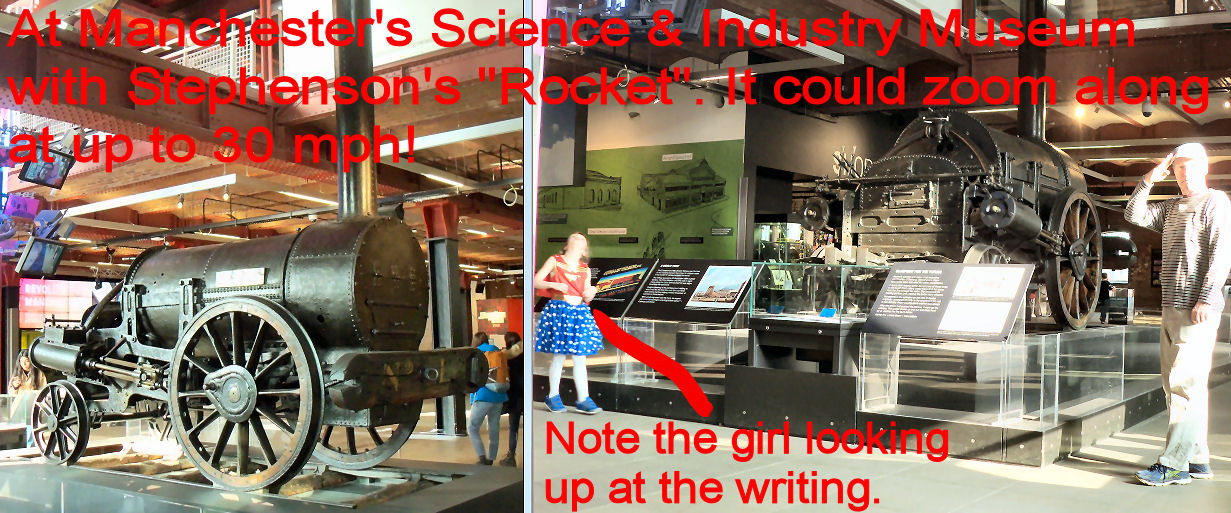

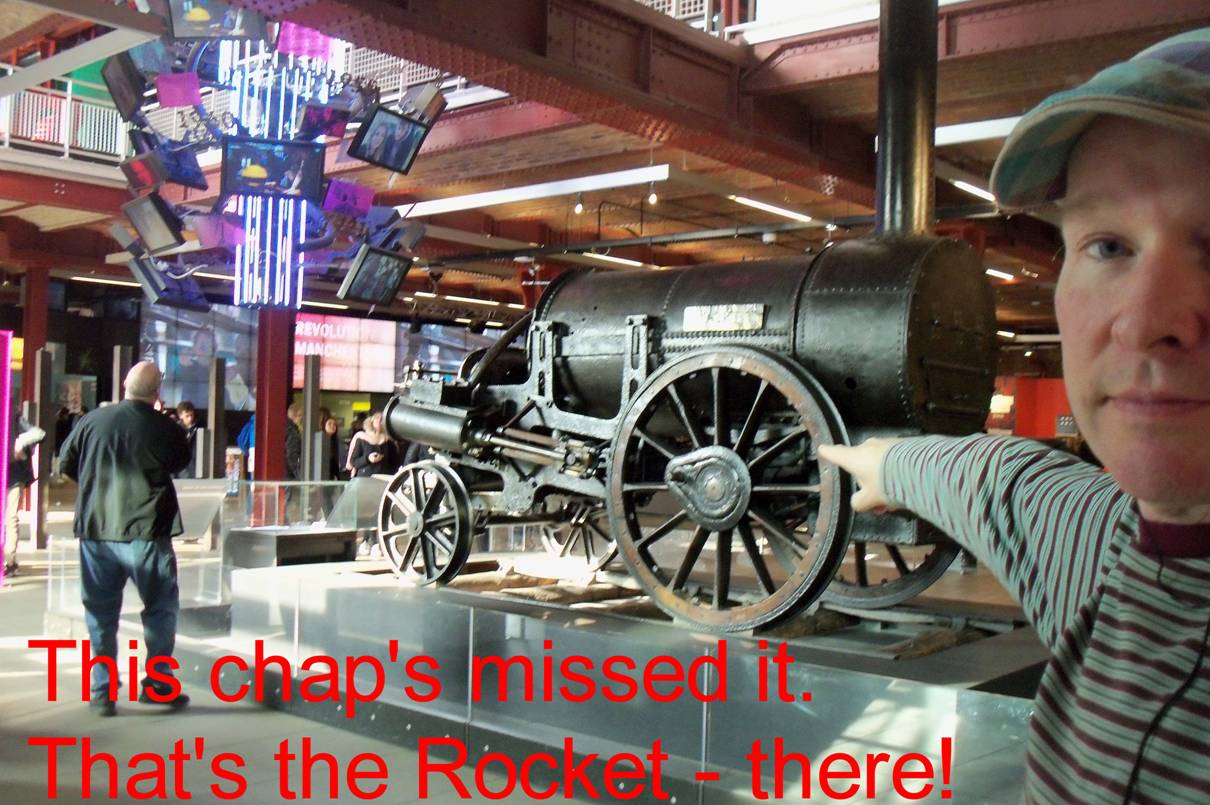

In 2019 I went to have a look

at Stephenson’s Rocket engine which

was on show at Manchester's Science & Industry Museum. I would have spent

the afternoon there but there must have been a problem with the drains as there

was a foul smell. I had a good look at the famous locomotive Rocket engine

though. It was invented by George who known as the father of British steam

railways. The distance between nearly all the world railways sleepers is 4 feet

8 1/2 inches wide (1.435 m) due to George’s various rail inventions. Here I am

at the church where he lies (under the communion table) and the home where he

died.

He was born to parents who couldn't read and he was

17 years old by the time he could write. Aged 21 he was operating engines at a

coal mine. He started designing them in his spare time and by 27 he’d built his

first locomotive. It pulled heavy wagons of coal across a coal site but it was

a start. More engines and improvements followed and his reputation was in locomotion

too...so much so he was hired to build an 8-mile railway from Hettor coilery to Sunderland. An

engine was needed to propel itself and negate the need for horses. He was 42 by

the time this was completed and a working success. At the time coal wasn’t just

the King in Britain but an Emperor and coal pits were looking for efficient

ways to get it around the country. Aged 44 George completed the first

locomotive for the Stockton and Darlington Railway. For the first time

purpose-built passenger car (called Experiment) which pulled along some

dignitaries for the opening journey.

Where did the Rocket come from? Money is a

powerful incentive and when George was 48 he learnt the bosses of the Liverpool

and Manchester Railway were offering a £500 prize (now £70,000) and contract to

build the locomotives for the new railway. His entry was the Rocket which was

fast - 30phm at top speed! It won the competition. At the time it was most

famous machine in the world. After this George was bombarded with offers of

work and the busiest time of his life commenced (but I won’t go into it here.)

Over his life George was married three times, his

first two wives dying quite young. He had a son and daughter though the latter

died within a few weeks. By the time he married his third wife (who’d been his

housekeeper) he was wealthy. Sadly seven months after the wedding he contracted

pleurisy and died aged 67 at noon on Saturday 12th August 1848 at his home Tapton House in Chesterfield, Derbyshire.

George’s grave : I’m afraid the church where he’s

buried was locked so I didn’t fix my short-sighted eyes on his tomb. There’s a

memorial statue in the cemetery but I don’t think it counts. I prefer to see

where the bones lie forever (he’s buried under the communion table alongside

his second wife.) Afterwards I sat in the car and had a peanut-butter sandwich

and frothy coffee in sight of Chesterfield’s crooked spire.

George’s home. Not far from the church lies Tapton House. You head up a winding drive to reach the

house where he lived for his final ten years. There’s an innovation centre

there now but the house and grounds are still intact. The old heavy gates to

the house were closed but I give them a shove and one moved so I went in.

There’s a circle at the front of the place where horses and carriages brought

people to and from the main door. Thankfully the place doesn’t look to have

been butchered with additions or extensions. In its life Tapton

House has been a gentleman's residence, a ladies' boarding school and a

co-educational school. Nowadays Chesterfield Council rent it the rooms as

offices.

I strolled across the lawns at the rear and down

to the small golf course below. George was a keen gardener all his adult life and

here in the grounds he built hothouses where he grew exotic fruits. The house

and gardens are in keeping with a wealthy inventor though there was only him

and a son. There must have been a raft of gardeners and maids. I looked up at

the many windows and wondered which room George had died in. He did well,

developing railways which accelerated the Industrial Revolution. Privately he

also a kind and generous chap, financially supporting the wives and families of

(mostly) men who’d died in his employment due to accident or misadventure. I

did a salute and left.

At George's home where he lived for ten years (and died)...