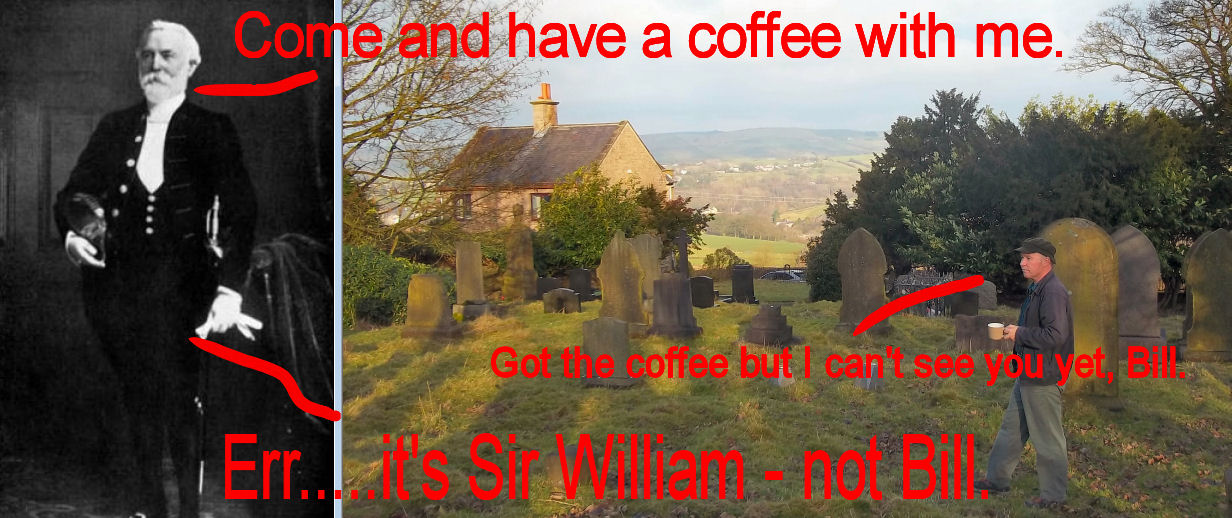

Sir

William Hartley (23rd February 1946 to 25th October 1922)

Whenever I'm out for the day I make

up sandwiches and a flask. My favourite sandwich filling is jam and cheese

(together) and the jam is usually Harltey’s. I can

remember Hartleys jams on the shelf in the shop my

mum ran forty years ago. The company is still flexing its muscles. Here I am at

a rural cemetery where the jam god Sir William Hartley is buried.

He’s buried just outside the small Lancashire

village of Colne where he was born in 1846, an only child.

Aged 14 he left school and worked for his mum and dad in the grocery business. Aged

20 he married Martha (the youngest of 13 children) and they’d go on to have six

children. He was 25 when the business started due to a chance event: a supplier

failed to deliver some jam so he made his own. It sold so well he started

making marmalade and jelly, too - all supplied in distinctive earthenware pots.

By the time he was 28 the business was doing well and, borrowing lots of money,

took a risk by transferring the manufacturing to Bootle in Merseyside.

The Hartley’s liked the coast and by the time

William was 34 the family had moved to Southport and became well known for

helping local causes and, being religious, were members of the local Methodist

Church. Aged 40 the business had made so much money they transferred

manufacturing to Aintree as it was near to the railway network (they had their

own siding.) Within five years another large warehouse was built and, eight

years later another. Often six trains arrived per day and two hundred wagons were

filled with jam and other conserves. William even chartered ships to get jam

across the world. Soon the factories were making 1000 tons of jam per year.

Being a devoted Christian William devoted Sundays

to the church. Like many religious businessmen he looked after his workers.

Aged 42 he had a model village at Aintree built for them (the cottages had

gardens, the streets were wide, there was a bowling green and playing fields

for sports.) He started a profit-sharing scheme, free medical treatment and

paid higher wages than those of his competitors. He made huge donations to

hospitals, universities and theological college (the one in Manchester is

called Hartley Victoria College.) At the jam factory he was known for being a

generous friendly man asking that anyone can approach him with problems inside

or outside the factory. He opened a benevolent fund to help those who were

suffering hardship (but this excluded anyone spending their wages on alcohol or

cigarettes.) When he learnt some workers lived too far away from home to nip

back for their dinner he built a huge cafe/dining room built that could seat

750 at a time (meals were at cost.)

In his seventies William was rich - so rich that

when World War One started the government was looking for financial

contributions to the effort. He made generous contributions but the war greatly

depleted staff that the jam factory was nearly lost. One profound personal loss

was that a grandson who was killed in action.

For years William had suffered from angina

pectoris but past resilience proved it wasn’t a grave worry. It was though and

the grave I’m stood beside beckoned with a crooked finger. One night his angina

was so bad his wife called into this bedroom three times but by the morning he

felt well enough to think about going to factory. Suddenly that Wednesday morning

he died of a heart attack aged 76. The jewel of the jam world was gone. The

funeral service was held near the Hartley home (since demolished) but the

funeral procession travelled 50 miles here to Trawden

outside Colne where I’m stood.

I’d looked for William’s grave years ago at the

main church in Colne. Slightly dejected I left and

only recently learnt of this overflow graveyard in the countryside. There’s no

church - just long-distance views across to Colne, fields

dotted with sheep and one house. There are bigger headstones in the small

graveyard but somehow I guessed which was William's. A few Hartley’s are buried

here judging by the fading carvings. Even in death William was helping people:

after his demise a Hartley Memorial Fund raised money to trained of medical

missionaries and impoverished students.

I found only one war grave - also one fencing in

a child hugely missed judging by the paraphernalia festooning it. I did salutes

and left.

Looking back to Colne...

The Hartley home where William

died...